Carlos González Ragel (Rajel)

b. 1899, Jerez de la Frontera, Spain; d. 1969, Ciempozuelos, Spain

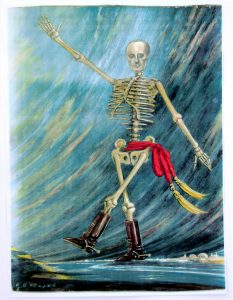

Carlos González Ragel (Rajel) was a painter, printmaker, photographer and designer who spent much of his life in psychiatric hospitals in Málaga, Seville and Ciempozuelos, where he died. Part of the bohemian and flamenco worlds, he designed posters and labels for wines and wineries in Jerez and produced an eccentric body of work which was always characterised by his Esqueletomaquias.

CONTRIBUTION

Esqueletomaquias, ca. 1937–42

5 albums, 20 drawings and 4 collages; facsimile reprints

Many of these drawings were presented at Carlos González Ragel’s 1937 exhibition in Seville, in the midst of the Civil War, with the city occupied by the fascists. The artist’s personal style – his representation of a world wholly through skeletons – casts doubt on the true status of his portraits of General Franco and Queipo de Llano, who embody death, enthroned on piles of corpses, which could nonetheless also be portraits of their triumph and glory. Ragel’s alcoholism and physical frailty led him to live for a long period under delirium tremens, which gave rise to the fantastical and visionary nature of his work. His Esqueletomaquias were his way of looking at the world in a traumatic fashion. According to him, the reason why his dances of the dead were mostly embodied by people from the world of parties, flamenco artists and ‘gypsy women’, had to do with keeping any kind of pessimism out of his work: the truly living dead. Although he was not familiar with José Guadalupe Posada, Ragel perfectly epitomised the popular nature of the Mexican artist’s works. Without consciously intending to, Ragel’s work accurately caricatured his time, and his own personal crises reflected the historical vicissitudes of the country he lived in: the early crises during the dictatorship of fellow Andalusian Primo de Ribera, the creative euphoria in the Republican years, despair and psychiatric confinement during and after the Civil War.

RELATED PLATFORMS